Acute Myeloid Leukaemia (AML) - Brief Information

Acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) is a malignant disease of the bone marrow. This text provides information about the characteristics and subtypes of the disease, its frequency, causes, symptoms, diagnoses, treatment, and prognosis.

Author: Maria Yiallouros, Editor: Maria Yiallouros, Reviewer: Prof. Dr. med. Ursula Creutzig, English Translation: Dr. med. habil. Gesche Tallen, Hannah McRae, Last modification: 2024/02/27 https://kinderkrebsinfo.de/doi/e77137

Table of contents

General disease information

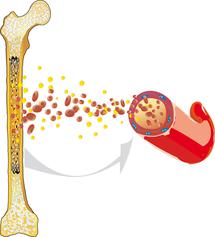

Acute myeloid (or nonlymphocytic) leukaemia (AML) is a malignant disease that arises within the haematopoietic system. AML usually originates from the bone marrow, where the blood cells are produced. It is characterised by an overproduction of impaired white blood cells.

Healthy blood cells reproduce and regenerate at a normal, balanced rate. They undergo a complex maturation process. AML interferes with this process: The white blood cells (leukocytes) are unable to mature into functional cells and instead multiply rapidly and uncontrollably. This disturbs normal blood cell formation, so that healthy white blood cells, red blood cells (erythrocytes), and platelets (thrombocytes) can no longer be produced to the extent that is necessary.

Anaemia, infections, and bleeding tendencies can result and may be the first signs of acute leukemia. Since AML is not limited to one specific region of the body, but can spread from the bone marrow into the blood and the lymphatic system, it can affect all organs and organ systems and is therefore – like all leukaemias – known as a malignant systemic disease.

AML progresses rapidly. The spread of leukaemia cells and the resulting damage to other body parts can cause serious diseases, which – without the appropriate treatment – are lethal within a few weeks or months.

Incidence

Comprising about 20 % of childhood leukaemia, acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) is, following acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL), the second most frequent leukaemia in children and adolescents. AML accounts for about 4 % of all cancers in this age group. According to the German Childhood Cancer Registry in Mainz, about 90 children and adolescents aged between 0 and 17 years are newly diagnosed with AML every year.

In general, AML can occur at any age, with a peak during adulthood. The frequency of childhood AML is highest during the first two years of life. After that, incidence decreases and remains stable throughout childhood. It shows a mild increase again during adolescence. The young patients’ average age at diagnosis is approximately seven years. Boys are slightly more affected than girls (sex ratio: 1,1 : 1). .

Types of acute myeloid leukaemia

AML is caused by a malignant transformation of immature “myeloid cells”. These are blood precursor cells in the bone marrow (blood stem cells), which finally develop either into red blood cells (erythrocytes), certain types of white blood cells (granulocytes or monocytes), or platelets (thrombocytes), depending on which kind of precursor myeloid cell is involved.

AML is mainly characterised by a malignant transformation of granulocyte precursor cells (so-called myeloblasts). However, AML can derive from any immature myeloid cell, i.e. from monocytes, young red blood cells or platelets, and even from the very young precursor (stem) cell of all of them. Furthermore, the development of immature into mature blood cells of any kind comprises several developmental stages, each of which can be affected by malignant transformation. This is why there are different forms of AML, such as acute myeloblastic, monocytic, erythroid, or megacaryocytic leukaemia and many more, including various mixed forms.

Eight major subtypes of AML are differentiated based on how the leukaemia cells look under the microscope, meaning based on their morphological appearance; in the past, these were relevant for the classification of AML. Today, classification is carried out based on both the morphological and cytogenetic as well as molecular genetic features of the abnormal cells.

Good to know: Various subtypes of childhood AML have been characterised so far, the courses and prognoses of which can differ significantly. Current treatment strategies for children and adolescents with AML consider these different subtypes. Therefore, children and adolescents with AML do not all receive the same treatment.

Causes

The causes of acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) are largely unknown. It is known so far that the disease arises from the malignant transformation of certain (myeloid) precursor blood cells in the bone marrow, and also, that this transformation can be associated with genetic alterations of these cells. Why these genetic alterations exist and why they cause the disease in some children but not in others, remains to be discovered. Most certainly, AML is caused by a specific combination of many genetic factors, that have not yet been identified.

AML is primarily not an inherited disease. However, the risk of developing this type of malignancy is increased in individuals with a positive family history for cancer: for example, siblings of a child with leukaemia have a slightly increased risk (about 1.1-fold) to develop leukaemia as well. The identical twin of a leukaemia patient has a risk of 15 % to also develop this disease. Therefore, it is recommended to check on blood and maybe even on bone marrow of the healthy twin, too.

It is known that children with certain inherited or acquired immunodeficiencies [immunodeficiency] as well as young patients with chromosomal abnormalities have a higher risk of developing acute leukaemia than their healthy peers. Hereditary concomitant diseases promoting the development of AML are, for example, Down syndrome, Fanconi anaemia, neurofibromatosis or monosomy 7. Since these (very rare) diseases are associated with a predisposition to develop cancer, they are also called cancer predisposition syndromes.

Both radiation therapy (radiotherapy) and chemotherapy given in childhood harbour a certain risk to develop a secondary malignancy later in life. For example, AML can develop as a secondary malignancy after radio- and/or chemotherapy of a different malignancy, such as an acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) or Hodgkin lymphoma. These forms of AML are also known as treatment-induced secondary AML. Also (prenatal exposure to) radioactive radiation or X-rays and to certain genotoxic chemicals and drugs, prenatal exposure to parental nicotine or alcohol abuse, and maybe certain viruses have been reported to play a role in the development of leukaemia. However, for most of the patients, no specific risk-factor for the development of AML has been identified yet.

Symptoms

The health problems (symptoms) caused by of most children and adolescents with AML develop within only a few weeks. They mainly occur due to the increase of malignant cells within the bone marrow as well as their spread into other organs and tissues. The uncontrolled production of leukaemia cells in the bone marrow increasingly suppresses the production of normal blood cells.

Children and adolescents suffering from AML initially experience general symptoms such as fatigue, pain, and pallor. This is due to the lack of red blood cells (anaemia), the function of which it is to carry oxygen to cells throughout the body. The lack of functional white blood cells (i.e. lymphocytes and granulocytes) prevents pathogens from being attacked and eliminated properly, thereby causing infections and fever. Another frequent symptom is bleeding, for example, under the skin (bruises, petechiae) or from mucous membranes such as the gums, owing to impaired blood coagulation as a result of low platelet counts.

The growth of leukaemia cells in the marrow of the long bones can cause bone and joint pain, especially in the limbs (arms and legs) and back. This pain can be so intense that the affected child may refuse to walk or run. The malignant cells can also spread into the liver, spleen, and lymph nodes. Therefore, these organs may enlarge and subsequently cause problems, such as abdominal pain. In general, all organs can potentially be affected by AML. If AML spreads to the brain and its meninges, patients may suffer from headache, visual disturbances, nausea, vomiting, and other central nervous system impairments.

Presenting symptoms in patients with AML are as follows:

Very frequent (over 60 % of patients):

- fatigue, exhaustion, weariness, malaise, pallor (caused by the lack of red blood cells, anaemia)

- fever and/or frequent nonspecific infections (due to the lack of white blood cells, neutropenia)

- abdominal pain and loss of appetite (due to the enlargement of spleen and/or liver)

Frequent (between 20 and 60 % of patients)

- increased risk of bleeding, for example, frequent spontaneous nose bleeding, gum bleeding (for example while brushing teeth), excessive bruising, pinpoint, round and red spots on the skin (petechiae); rare: cerebral haemorrhage (due to lack of platelets)

- enlarged lymph nodes (for example, in neck, armpits, groin)

- bone and joint pain (mostly limbs and back)

Rare (under 20 % of patients)

- headache, visual disturbances, vomiting, cranial nerve palsies (due to involvement of the central nervous system)

- shortness of breath (in case of high count of white blood cells, hyperleukocytosis)

- skin changes and chloroma (myeloid blastoma or myeloud sarcoma): tumour-like local masses of leukaemia cells in the skin, lymph nodes, bone, and, sometimes around the eyes; coloured, partly bluish-green in colour

- gingival (gum) enlargement (gingival hyperplasia)

- enlargement of testicles

Good to know: The type and degree of symptoms of AML vary individually. It is also important to know that a child or teenager showing one or more of these symptoms does not necessarily suffer from AML. Many of the symptoms described above, such as fever, fatigue, or headaches, are also regularly seen with frequent and rather harmless childhood diseases, like common colds and other viral infections. Nevertheless, if these symptoms recur frequently or persist,a doctor should be consulted as soon as possible. If acute leukaemia is diagnosed, treatment must be started promptly.

Diagnosis

If the doctor, based on the young patient’s history (anamnesis) and physical examination, suspects acute leukaemia, he or she will first initiate a blood test (blood count). If the results promote the diagnosis of an acute leukaemia, a sample of the bone marrow (bone marrow puncture) is required for confirmation. For bone marrow tests and other diagnostic procedures, the doctor will refer the patient to a children's hospital with a childhood oncology program (paediatric oncology unit) and childhood cancer specialists.

Blood and bone marrow tests

Blood and bone marrow tests are needed to confirm the diagnosis of leukaemia as well as to determine the type. The tests include microscopic (cytomorphological), immunological, and genetic laboratory analysis of blood and bone marrow samples that distinguish AML from other kinds of leukaemia (such as ALL) and, furthermore, allow to define the specific subtype of AML. Knowing the subtype of AML is necessary for appropriate therapy planning, because different forms of AML have different biological characteristics and also vary regarding their response to treatment and, thus, prognosis.

Tests to assess spread of the disease (staging)

Following the diagnosis of AML and its subtype, it is important for treatment planning to know whether the leukaemia cells have spread to additional body compartments (other than the bone marrow), including the brain, liver, spleen, lymph nodes, testicles, or bones. Therefore, various imaging techniques, such as ultrasound, X-ray examination, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and/or computed tomography (CT), may be used to evaluate spread of the disease. To find out whether the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord) is affected, a sample of cerebrospinal fluid is taken and analysed for leukaemia cells (lumbar puncture).

Additional diagnostics before treatment begins

To prepare the patient for the intensive treatment, several organ functions must be checked, since certain anticancer agents have specific side effects that can damage different organs. To have an initial assessment later helps to detect and appropriately interprete potential functional changes. These preparatory diagnostics usually include various tests of the heart function (such as electrocardiography (ECG) and echocardiography) and the brain function (electroencephalography, EEG) as well as a variety of different blood tests that will give information on how well liver, bone marrow, and kidneys are working. Furthermore, the patient’s blood group will be defined, which is essential in case a blood transfusion may be necessary during the course of treatment.

Good to know: Not all the tests listed above need to be done for every patient. Contrariwise, the patient’s individual situation may require additional diagnostic procedures that have not been mentioned in this chapter. Therefore, you should always ask your doctor, based on the information above, which test your child needs and why.

Treatment planning

After the diagnosis has been confirmed, therapy is planned. In order to design an individual, risk-adapted treatment regimen for the patient, certain factors influencing the patient’s chance of recovery (prognosis) – called risk factors or prognostic factors – are being considered during treatment planning (risk-adapted treatment strategy).

Important prognostic factors are the subtype of AML (see chapter „types of acute myeloid leukaemia“), the extent of leukemia cell spread throughout the body at diagnosis, and the response of the disease to chemotherapy. The exact knowledge of the tumour type helps the caregiver team to assess how sensitive the tumour cells might be to the chemotherapy and, thus, how intensely patients need to be treated in order to keep the risk of relapse as low as possible. Extent of the disease and response to treatment impact the decision whether, aside from chemotherapy, additional treatment methods (for example radiation therapy of the brain or high-dose chemotherapy followed by stem cell transplantation) are necessary to increase the probability of cure.

All these factors are included in treatment planning in order to achieve the best outcome possible for each patient. Hence, each individual clinical situation is crucial for assigning a patient to the appropriate treatment group and for choosing the optimal treatment protocol, in order to guarantee he or she will receive the most appropriate (risk-adapted) treatment. Currently, three treatment groups are differentiated: standard-risk group, medium- (intermediary-)risk group, and high-risk group.

Treatment

If acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) is being suspected or has been diagnosed, treatment should be started as soon as possible in a children's hospital with a paediatric oncology program. Only in such a treatment centre, highly experienced and qualified staff (doctors, nurses and many more) is guaranteed, since they are specialised and focus on the diagnostics and treatment of children and teenagers with cancer according to the most advanced treatment concepts. The doctors (such as oncologists, radiologists, surgeons) in these centres collaborate closely with each other. Together, they treat their patients according to treatment plans (protocols) that are continuously optimised. The goal of the treatment is to achieve high cure rates as well as low rates of side effects.

Treatment methods

Chemotherapy is the major backbone of AML treatment. It uses drugs (so-called cytostatic agents or cytostatics) that can kill fast-dividing cells, such as cancer cells, or inhibit their growth, respectively. Since one cytostatic agent alone may not be capable of destroying all the leukaemia cells, a combination of cytostatics that function in different ways are usually given (polychemotherapy).

Specific treatment concepts for patients with Down syndrome or APL: AML patients with Down syndrome do not require a chemotherapy as intensive as other patients with AML do. Patients with acute promyelocytic leukaemia (APL) – a subtype of AML – may do completely without chemotherapy. They receive other substances instead.

Radiation therapy of the brain (cranial irradiation) is performed in few cases in addition to chemotherapy to treat central nervous system involvement, for example, when their central nervous system is obviously involved. High-dose chemotherapy followed by stem cell transplantation may be an option for patients who do not respond to treatment from the very beginning or who develop recurrent disease.

The major goal of treatment is to eliminate the leukaemia cells in the body as extensively as possible, so that the bone marrow can resume its function as a blood cell-producing organ. In order to prevent or adequately manage the side effects of the intensive therapy, specific supportive care regimens have been established and now represent an important and efficient component of AML treatment.

Good to know: The intensity and duration of chemotherapy, the need for radiation therapy and/or stem cell transplantation, as well as the prognosis of the disease, depend on the subtype of AML, on how extensively the leukaemia cells have spread throughout the body, whether the patient tolerates the treatment, and whether the leukaemia responds to it (see chapter "Treatment planning").

Treatment courses

In general (i.e. apart from for above-mentioned specific cases), treatment of children and teenagers with AML consists of different steps. These steps (or phases) have different purposes. Therefore, they vary regarding their duration, treatment intensity, and the drug combinations applied. Major treatment elements are:

- Induction therapy: Induction consists of an intensive chemotherapy with various anticancer agents (polychemotherapy). It aims at achieving remission, i.e. elimination of most of the leukaemia cells, in a relatively short period of time. Induction therapy usually takes about two months, comprising two courses of chemotherapy, with a phase of recovery in between.

- Consolidation therapy: Consolidation follows induction therapy. It includes three courses of intensive chemotherapy, however, partially with different agents than those used during induction. With consolidation therapy, which takes about three to four months, the remaining leukaemia cells are to be further reduced, thus minimising the patient's risk of developing recurrent disease.

- CNS-directed therapy: Treatment of the central nervous system (CNS-directed therapy) is recommended for all patients with AML. It is meant to either prevent a spread of leukaemia cells to the CNS (prophylactic treatment) or, in case the CNS is already affected, to stop them from being dispersed any further (therapeutic treatment). In any case, CNS-treatment occurs during systemic therapy and includes the application of anticancer drugs into the spinal canal via a lumbar puncture (intrathecal chemotherapy). If the CNS is definitely involved, radiotherapy of the brain is recommended in addition to intrathekal chemotherapy. Radiation takes about two to three weeks and is carried out subsequent to consolidation therapy.

- Maintenance therapy: Maintenance therapy consists of a less intense polychemotherapy. It is mostly given orally while the children are out-patients. The goal of performing maintenance therapy is to fight all leukaemia cells that might have survived the intensive treatment over a long period of time, usually about a year after cessation of intensive therapy. Important note: Recently, maintenance therapy has no longer been part of the treatment!

Some patients, for example children with high numbers of leukaemia cells (high white blood cell counts) at diagnosis or patients with severe involvement of other organs, receive a so-called pretreatment prior to the induction therapy (cytoreductive preliminary phase). The treatment consists of a short, approximately one week long, phase of chemotherapy using moderate dosages of one or two different agents. The purpose of this phase is to reduce the often initially heavy burden of leukaemia cells gradually. This relatively gentle start helps the doctors to keep the metabolic products released by the dying leukaemia cells under control, which is important, because such metabolites can seriously harm the patient's organs, especially the kidneys (so-called tumour lysis syndrome).

The overall treatment time is about half a year without maintenance therapy (as long as no stem cell transplantation is required, the patient responds to therapy and does not suffer disease relapse). These intensive six months of treatment require various times as an inpatient. Recovery breaks between chemotherapy cycles, however, can be spent at home as long as the patient does not experience any serious complications such as fever and/or infections. During the moderately intense, longer time (about a year) of maintenance therapy, which until recently formed part of the treatment, the patient was allowed be at home. However, regular follow-up visits in the outpatient clinic were to be attended.

Therapy optimising trials and registries

In Germany, diagnosis and treatment of almost all children and adolescents with first diagnosis of acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) are performed according to the treatment plans (protocols) of therapy optimising trials, so named because the treatment concepts of such trials are continously being optimised based on the respective current status of medical knowledge. Therapy optimising trials are standardised, controlled studies which aim at steadily developing and improving treatment possibilities for cancer patients. With many treatment centres being involved, such trials are also called "multicenter" or "multicentric" trials, and most often many countries participate.

Patients who are not included in any trial, either because they suffer disease while there is no trial available or because they do not, for some reason, fit into one of the existing trials, are often included in so-called registries. The patients are generally treated according to the recommendations of the trial centre, thus receiving the current best therapy available.

Currently, the following therapy optimising trials and registries are available for children and adolescents with AML in Germany:

- AIEOP-BFM-AML 2020: Since the end of February 2023, children and adolescents with AML can be included in the international therapy optimising trial AIEOP-BFM-AML 2020. Eligible are patients (under 18 years) with primary AML diagnosis and patients (under 21 years) with AML relapse, respectively. AML patients with acute promyelocyte leukaemia, Down syndrome, and/or a transient myeloproliferative syndrome are not included. Aim of the study is to increase cure rates as well as to reduce side-effects of the treatment by means of new agents or such with a different mechanism of action. Numerous treatment centres throughout Germany as well as other European countries participate in this trial.

- Registry AML-BFM 2017: Since the beginning of 2018, all AML patients under 18 years of age can register in the registry AML-BFM 2017 (which is the subsequent version of the registry AML-BFM 2012). This applies to patients with primary AML diagnosis as well as with AML relapse or AML as a secondary malignancy, respectively. The registry also documents patients with acute promyelocytic leukaemia (APL) and patients with down syndrome and AML, if they are not treated within a trial (see below). Infants with Down syndrome, who have been diagnosed with a so-called transient myeloproliferative syndrome (TMD), are registered as well. TMD is a disease that frequently transforms into an AML. The registry aims at collecting disease- and treatment-associated data of as many AML patients as possible in order to further optimise the understanding and treatment of the disease. It also provides treatment recommendations for patients who are not eligible for / participating in any trial in order to maintain optimal treatment options for them.

- Trial ML-DS 2018: For children with Down syndrome and AML (briefly ML-DS), the therapy optimising trial ML-DS 2018 has been open since February 2018. Eligible are patients with or without GATA1 mutation who are older than 6 months and younger than 4 years of age OR patients with GATA1 mutation who are older than 4 years and younger than 6 years of age. Goal of the study is to analyse whether reducing treatment intensity, and thereby further minimizing side effects, is an option for patients with good response to therapy. Multiple treatment centres throughout Germany and other European countries are participating in this trial.

Note: The trial centre for AIEOP-BFM-AML 2020 and the registry is located at the University Hospital Essen (principal investigator: Prof. Dr. med. Dirk Reinhardt). Trial ML-DS 2018 is supervised by Prof. Dr. Jan-Henning Klusmann (University Hospitals Halle (Saale) and Frankfurt/Main).

Prognosis

Thanks to the immense progress in diagnostics and treatment over the last four decades, the chances of cure for children and adolescents with acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) have significantly improved. Today’s modern diagnostic procedures and the use of intensive, standardised polychemotherapy protocols combined with optimised supportive care regimens result in current 5-year survival rates of 75 to 80 %.

However, this also means that in approximately 20 to 25 % of the young patients the disease cannot be controlled, which is mainly due to the high rates of disease relapses: nearly one third of the children and adolescents diagnosed with AML in Germany per year suffer recurrent disease. Furthermore, about 10 % of patients do not respond to therapy and, thus, do not attain remission after the intensive treatment phase.

The individual prognosis of a patient primarily depends on the genetic subtype of AML as well as on how well the disease responds to therapy. Patients with favourable genetic subtype and good treatment response can achieve cure rates up to 90 %. The cure rates for patients with unfavourable prognostic factors, however, are far beyond 70 %, even when treated according to intensified regimens. Due to their low risk of relapse, patients with newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukaemia (APL) have a 10-year-survival rate of more than 90 % and, thus, a far better prognosis than patients with other AML subtypes.

In case of a relapse, prognosis is generally worse, in particular, if the disease comes back early, such as within a year after achievement of the first remission. This also applies to patients with no response to therapy. However, prognosis after relapse has improved during the last decade due to better therapy regimens including stem cell transplantation. The 5-year survival rates in children and adolescents with AML relapse are currently in the range of 40 %. The major goal of the current therapy optimising trials and future studies is to find ways to further improve the chances of cure for all AML patients, including those with recurrent disease.

Note: The survival rates mentioned in the text above are statistical values. Therefore, they only provide information on the total cohort of patients with childhood AML. They do not predict individual outcomes. Acute leukaemias can show unpredictable courses, in both patients with favourable and patients with unfavourable preconditions.

PDF Brief information on Akute Myeloblastic Leukaemia (AML) (474KB)

PDF Brief information on Akute Myeloblastic Leukaemia (AML) (474KB)

Author: Maria Yiallouros

18/01/2024

References

- Stanulla M, Erdmann F, Kratz CP: Risikofaktoren für Krebserkrankungen im Kindes- und Jugendalter. Monatsschrift Kinderheilkunde 169, 30-38 2021 [DOI: 10.1007/s00112-020-01083-8]

- Rasche M, Zimmermann M, Steidel E, Alonzo T, Aplenc R, Bourquin JP, Boztug H, Cooper T, Gamis AS, Gerbing RB, Janotova I, Klusmann JH, Lehrnbecher T, Mühlegger N, Neuhoff NV, Niktoreh N, Sramkova L, Stary J, Waack K, Walter C, Creutzig U, Dworzak M, Kaspers G, Kolb EA, Reinhardt D: Survival Following Relapse in Children with Acute Myeloid Leukemia: A Report from AML-BFM and COG. Cancers 2021 May 12; 13 [PMID: 34066095]

- Erdmann F, Kaatsch P, Grabow D, Spix C: German Childhood Cancer Registry - Annual Report 2019 (1980-2018). Institute of Medical Biostatistics, Epidemiology and Informatics (IMBEI) at the University Medical Center of the Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz 2020 [URI: https://www.kinderkrebsregister.de/ typo3temp/ secure_downloads/ 42507/ 0/ 1c5976c2ab8af5b6b388149df7182582a4cd6a39/ Buch_DKKR_Jahresbericht_2019_komplett.pdf]

- Creutzig U, Dworzak M, Reinhardt D: Akute myeloische Leukämie (AML) im Kindes- und Jugendalter. Leitlinie der Gesellschaft für Pädiatrische Onkologie und Hämatologie AWMF [URI: https://www.awmf.org/ uploads/ tx_szleitlinien/ 025-031l_S1_Akute-myeloische-Leukaemie–AML–Kinder-Jugendliche_2019-09.pdf]

- Creutzig U, Dworzak M, von Neuhoff N, Rasche M, Reinhardt D: [Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia: New treatment strategies with ATRA and ATO - AML-BFM-Recommendations]. Klinische Padiatrie 2018, 230: 299 [PMID: 30399642]

- Creutzig U, Reinhardt D: Akute myeloische Leukämien, in Niemeyer CH, Eggert A (Hrsg.): Pädiatrische Hämatologie und Onkologie. Springer-Verlag GmbH Deutschland 2018 [ISBN: 3540037020]

- Uffmann M, Rasche M, Zimmermann M, von Neuhoff C, Creutzig U, Dworzak M, Scheffers L, Hasle H, Zwaan CM, Reinhardt D, Klusmann JH: Therapy reduction in patients with Down syndrome and myeloid leukemia: the international ML-DS 2006 trial. Blood 2017 Jun 22; 129: 3314 [PMID: 28400376]

- Creutzig U, Dworzak MN, Bochennek K, Faber J, Flotho C, Graf N, Kontny U, Rossig C, Schmid I, von Stackelberg A, Mueller JE, von Neuhoff C, Reinhardt D, von Neuhoff N: First experience of the AML-Berlin-Frankfurt-Münster group in pediatric patients with standard-risk acute promyelocytic leukemia treated with arsenic trioxide and all-trans retinoid acid. Pediatric blood & cancer 2017, Epub ahead of print [PMID: 28111878]

- Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, Thiele J, Borowitz MJ, Le Beau MM, Bloomfield CD, Cazzola M, Vardiman JW: The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood 2016 May 19; 127: 2391 [PMID: 27069254]

- Creutzig U ,Zimmermann M, Dworzak MN, Ritter J, Schellong G, Reinhardt D: Development of a curative treatment within the AML-BFM studies. Klinische Padiatrie 2013, 225 Suppl 1:S79 [PMID: 23700063]

- Rossig C, Jürgens H, Schrappe M, Moericke A, Henze G, von Stackelberg A, Reinhardt D, Burkhardt B, Woessmann W, Zimmermann M, Gadner H, Mann G, Schellong G, Mauz-Koerholz C, Dirksen U, Bielack S, Berthold F, Graf N, Rutkowski S, Calaminus G, Kaatsch P, Creutzig U: Effective childhood cancer treatment: The impact of large scale clinical trials in Germany and Austria. Pediatric blood & cancer 2013, 60: 1574 [PMID: 23737479]

- Kaspers GJ, Zimmermann M, Reinhardt D, Gibson BE, Tamminga RY, Aleinikova O, Armendariz H, Dworzak M, Ha SY, Hasle H, Hovi L, Maschan A, Bertrand Y, Leverger GG, Razzouk BI, Rizzari C, Smisek P, Smith O, Stark B, Creutzig U: Improved Outcome in Pediatric Relapsed Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Results of a Randomized Trial on Liposomal Daunorubicin by the International BFM Study Group. J Clin Oncol 2013, 31: 599 [PMID: 23319696]

- Creutzig U, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, Gibson B, Dworzak MN, Adachi S, de Bont E, Harbott J, Hasle H, Johnston D, Kinoshita A, Lehrnbecher T, Leverger G, Mejstrikova E, Meshinchi S, Pession A, Raimondi SC, Sung L, Stary J, Zwaan CM, Kaspers GJ, Reinhardt D, AML Committee of the International BFM Study Group: Diagnosis and management of acute myeloid leukemia in children and adolescents: recommendations from an international expert panel. Blood 2012, 120: 3187 [PMID: 22879540]

- Reinhardt D, Von Neuhoff C, Sander A, Creutzig U: [Genetic Prognostic Factors in Childhood Acute Myeloid Leukemia]. Klinische Padiatrie 2012, 224: 372 [PMID: 22821298]

- Niewerth D, Creutzig U, Bierings MB, Kaspers GJ: A review on allogeneic stem cell transplantation for newly diagnosed pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 2010, [PMID: 20538803]

- Sander A, Zimmermann M, Dworzak M, Fleischhack G, von Neuhoff C, Reinhardt D, Kaspers GJ, Creutzig U: Consequent and intensified relapse therapy improved survival in pediatric AML: results of relapse treatment in 379 patients of three consecutive AML-BFM trials. Leukemia 2010 [PMID: 20535146]

- von Neuhoff C, Reinhardt D, Sander A, Zimmermann M, Bradtke J, Betts DR, Zemanova Z, Stary J, Bourquin JP, Haas OA, Dworzak MN, Creutzig U: Prognostic Impact of Specific Chromosomal Aberrations in a Large Group of Pediatric Patients With Acute Myeloid Leukemia Treated Uniformly According to Trial AML-BFM 98. Journal of clinical oncology 2010, 28: 2682 [PMID: 20439630]

- Zwaan MC, Reinhardt D, Hitzler J, Vyas P: Acute leukemias in children with down syndrome. Pediatric clinics of North America 2008, 55: 53 [PMID: 18242315]

- Belson M, Kingsley B, Holmes A: Risk factors for acute leukemia in children: a review. Environmental health perspectives 2007, 115: 138 [PMID: 17366834]