Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma (NHL) – Brief Information

Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma (NHL) are malignant diseases of the lymphatic system. This text provides information about the characteristics and subtypes of the disease, its frequency, causes, symptoms, diagnoses, treatment, and prognosis.

Author: Maria Yiallouros, Reviewer: Prof. Dr. med. Birgit Burkhardt; Prof. Dr. med. Wilhelm Wößmann; PD Dr. med. Alexander Claviez, English Translation: Dr. med. Gesche Riabowol (nee Tallen), Last modification: 2024/02/27 https://dx.doi.org/10.1591/poh.patinfo.nhl.kurz

Table of contents

General disease information

Non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL) are cancerous (malignant) diseases of the lymphatic system. They belong to the group of malignant lymphomas. „Malignant lymphoma“ literally means „malignant tumour of the lymph node“. In medical jargon, the term summarises all cancers that arise from cells of the lymphatic system (lymphocytes) and that can cause lymph node swelling.

Malignant lymphomas are classified into two major groups: Hodgkin lymphoma, which is named after the physician and pathologist Dr. Thomas Hodgkin, and the Non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL). The latter include, as implied by their name, all malignant lymphomas that do not reveal the characteristics of Hodgkin lymphoma. Differentiation between these two types of lymphomas is only possible by analysing the lymphoma tissue under the microscope (histological examination).

NHL develop from malignantly transformed lymphocytes, a type of white blood cells (leukocytes) found in blood and lymphatic tissue. NHL can arise from every organ comprised of lymphatic tissue. Most frequently affected are the lymph nodes, but other organs (for example the spleen, thymus gland, tonsils, and the Peyer’s patches in the small intestines) can develop NHL as well.

Very rarely, NHL are found as circumscribed tumours at a certain site of the body. They rather tend to spread from their primary site to many other organs and tissues, such as the bone marrow, the liver, or the central nervous system. Therefore, they are, as are leukaemias, considered as systemic malignancies. Their biological behaviour is very similar to that of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL).

Almost all NHL in children and adolescents are highly malignant, meaning that they spread fast, thereby causing severe complications, which are lethal if not treated appropriately. Low-grade NHL with slow spread, as seen mostly in adults, are rather rare in childhood and adolescence.

Incidence

According to the German Childhood Cancer Registry in Mainz, about 145 children and adolescents younger than 18 years are newly diagnosed with Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) in Germany per year. Thus, NHL account for approximately 6,4 % of all paediatric malignancies in this age group. Also, there are B-cell leukaemias (Burkitt leukaemias), which are treated like NHL and account for about 0.5 %, meaning 10-11 reported new diagnoses per year.

NHL can develop at any age. They mostly affect children who are older than four years. Prior to the third year of age, NHL are rather rare. Boys develop the disease more than twice as often as girls. This ratio can vary, however, depending on the type of NHL.

Causes

The causes of Non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL) still have to be elucidated. It is known so far that the disease arises from the malignant transformation of cells in the lymphatic system, the lymphocytes, and also, that this transformation is associated with genetic alterations of these cells. Why these genetic alterations exist and why they cause the disease in some children, but not in others, is not known yet. Most certainly, NHL are caused by a specific combination of many factors.

Children with certain congenital diseases of the immune system (such as Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, Louis-Bar syndrome) are known to have higher risk of developing a NHL. Since these (very rare) hereditary diseases are associated with a higher predisposition to develop cancer, they are also called cancer predisposition syndromes. Also, acquired immune deficiencies (for example due to HIV infection) and intensive immunosuppressive treatments (for example in the context of an organ transplantation or, less frequently, a stem cell transplantation), are connected with a higher risk for a Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma.

Furthermore, viruses, radioactive radiation, certain chemical substances, and drugs can play a role in the development of an NHL. However, for the majority of patients, no specific risk factor has been established yet.

Symptoms

Highly malignant Non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL) are highly aggressive tumours, which grow and spread fast to different body sites, thereby causing either visible tumours or other health problems (symptoms).

First sign of the disease is usually a painless swelling of one or more lymph nodes.

Lymph node swellings due to NHL can appear in the head and neck area, at arms and legs, in the armpits, the groins or at multiple sites at the same time. The disease can also arise from lymph nodes that cannot be seen or palpated at all, such as those in the chest or abdomen. Large lymph nodes in the abdomen may present as tummy aches, indigestion, nausea, and vomiting as well as back pain. Sometimes they can compress the intestines and cause an intestinal obstruction. If lymph nodes in the chest are affected, for example in the so-called mediastinum, which is the space between the lungs, the resulting pressure on airways and lungs can lead to cough and breathing difficulty. Similar symptoms occur if the thymus gland, lungs, and upper airways are affected.

Frequently, other lymphatic and non-lymphatic organs and tissues are involved as well. For example, spleen and liver may be enlarged due to the infiltration by lymphoma cells (splenomegaly, hepatomegaly). Also, the membranous coverings of the brain and spinal cord (meninges) can be affected in patients with NHL; as a consequence, headaches, facial weakness, visual deficits, and/or vomiting may occur. Infiltration of bony tissue can cause musculoskeletal pain.

In some patients, the number of healthy white blood cells is reduced; these patients are therefore prone to infections. In case of extensive bone marrow infiltration, red blood cell and/or platelet count(s) can be low as well. Lack of red blood cells leads to anaemia, whereas a lack of platelets can present as pinpoint round spots on the skin (petechiae) caused by bleeding.

Aside from above symptoms, patients may experience more general signs of illness, such as fever, unintended weight loss, night sweats, and fatigue. Three of these frequently occur together in patients with NHL: fever (higher than 38°C), drenching night sweats, and unintended weight loss of more than 10 % over the last six months. This combination of symptoms is also known as the B-symptoms.

The following overview summarizes the most frequent symptoms caused by Non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

General symptoms

- fever of unknown origin (over 38°C, persisting or recurrent) [B-symptom]

- night sweats [B-symptom]

- unexplained weight loss (more than 10 % in six consecutive months prior to admission) [B-symptom]

- fatigue, listlessness, loss of appetite, malaise

Specific symptoms

- painless, palpable packages of swollen lymph nodes, for example in the area of the head or neck, in the armpits or groins

- abdominal pain, diarrhea or constipation, vomiting and loss of appetite (if abdominal lymph nodes or organs, such as liver or spleen, are involved)

- chronic cough, shortness of breath (if thoracic lymph nodes, thymus gland, lungs or respiratory tract are involved)

- bone or joint pain (if bones are involved)

- headache, visual disturbances, vomiting (also on an empty stomach), cranial nerve palsies (due to involvement of the central nervous system)

- increased risk of infections due to lack of functional white blood cells

- pallor due to lack of red blood cells (anaemia; if the bone marrow is involved)

- pinpoint, round and red spots on the skin (petechiae) caused by an increased risk of bleeding due to lack of platelets

Good to know: Symptoms and complaints usually develop within a few weeks. They can vary individually with regards to type and intensity. However, the occurrence of one or more of the above-mentioned symptoms does not necessarily mean that they are caused by an NHL. Several of these symptoms, such as lymph node swelling and fever, are exactly those often seen with common childhood diseases like colds and other viral infections. Nevertheless, it is strongly recommended to have the child or teenager see a paediatrician, in particular, if symptoms persist or progress.

Diagnosis

If the paediatrician thinks that the young patient’s history (anamnesis) physical examination and possibly even results from blood tests, ultrasound and/or X-ray examination (radiographs) are suspicious of Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), the child should be referred to a hospital with a childhood cancer program (paediatric oncology program). If an NHL is suspected, a wide range of diagnostic tests is required not only to confirm the diagnosis, but also to assess the type of NHL and its extent of potential spread.

Obtaining a tumour sample (biopsy)

Two major procedures help confirming the diagnosis of an NHL: in case of excess liquid in the abdomen (ascites) or in the chest (pleural effusion), abdominal or pleural tapping are performed by needle aspiration for drainage and further fluid analysis, thereby bypassing a surgical procedure. In any case, a bone marrow specimen will be obtained, usually by bone marrow puncture, to check if there is any bone marrow involvement and if so, to which extent. If the bone marrow contains 25 % of lymphoblasts or more, the disease is classified as acute lymphoblastic B-cell leukaemia and will be treated as per assigned protocols. If no ascites, pleural effusion or bone marrow infiltration are found, affected lymph nodes or other affected tissue will be surgically removed for further analysis.

The tissue samples obtained by needle aspiration, bone marrow puncture, or surgery are analysed using cytological, immunohistochemical, immunological, and genetic methods in the laboratory. These analyses allow precise assessment of the patient's type of NHL. This is a major precondition for targeted treatment planning, since the various forms of NHL do not only differ with regard to their cellular and molecular characteristics, but are also associated with different courses of the disease, outcomes, and responses to treatment.

Tests to assess spread of the disease

Once the diagnosis of Non-Hodgkin lymphoma has been confirmed, further tests are required to find out if and to which extent the cancer has spread and which organs are involved. These tests include imaging, such as ultrasound and radiographs, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and/or computed tomography (CT). MRI and CT imaging are more and more routinely combined with positron emission tomography (PET scan), which helps detect lively, metabolising lymphoma tissue very effectively (so-called PET-MRI or PET-CT, respectively).

To evaluate potential central nervous system (CNS) involvement, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is obtained by lumbar puncture for further analysis. In addition, all patients undergo a bone marrow puncture to assess potential bone marrow involvement.

Tests before treatment begins

For treatment preparation, tests on the patient’s cardiac function (electrocardiography and echocardiography) are performed. Furthermore, additional blood tests are needed to assess the patient’s general health condition and to check whether the function of certain organs (such as liver and kidneys) is affected by the disease and whether there are any metabolic disorders or infections to be considered prior or during therapy. Any changes occurring during the course of treatment can be assessed and managed better based on the results of those initial tests, which thus help to keep the risk of certain treatment-related side effects as low as possible. Also, the patient’s blood group needs to be determined in case a blood transfusion is required during treatment.

Good to know: Not all the tests listed above need to be done for every patient. Contrariwise, the patient’s individual situation may require additional diagnostic procedures that have not been mentioned in this chapter. You should, therefore, always ask your doctor, based on the information above, which test your child needs and why.

Treatment planning

After having confirmed the diagnosis of a Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), the doctors will plan the treatment. In order to provide a therapy that is specifically designed for the patient’s individual situation (risk-adapted therapy), the doctors will take into consideration certain factors that have been shown to have an impact on the prognosis (so-called risk factors or prognostic factors).

Relevant prognostic factors and, thus, important criteria for NHL treatment are:

- the type of NHL: it determines the protocol as per which the patient should be treated

- the extent / potential spread (stage) of the disease: it determines the intensity and duration of the treatment

The following information gives an overview on the different types and stages of NHL.

Types of Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

Non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL) are classified into different subgroups based on certain characteristics. The international WHO classification differentiates between the following three major subgroups of NHL:

Aside from these three major subtypes, which are partially further differentiated, there are more, rare forms of NHL.

- Precursor B-cell and Precursor T-cell lymphoblastic lymphomas (B-LBL, T-LBL): these arise from immature precursors of B lymphocytes and T lymphocytes and are therefore closely related to the acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL). In Germany, they account for about 25-30 % of childhood NHL.

- Mature B-cell lymphomas and mature B-ALL: these develop from mature B-cells and comprise about 50-60 % of childhood NHL, thereby representing the most frequent NHL subtype in children and adolescents in Germany. Most frequent B-cell lymphomas are Burkitt lymphoma and the mature B-ALL.

- Mature T-cell lymphomas such as anaplastic large cell lymphomas (ALCL): these arise from mature T lymphocytes and account for about 10-15 % of all childhood NHL.

Aside from these three major subtypes, which are partially further differentiated, there are more, rare forms of NHL.

Good to know: The different NHL subtypes vary a lot with regard to the course and the outcome (prognosis) of the disease. Therefore, patients are assigned to three different treatment groups with different treatment plans, based on the NHL subtype that has been diagnosed. Hence, correct classification of NHL is crucial for choosing the right treatment.

Stages of Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

Staging of Non-Hodgkin lymphoma is crucial for both treatment planning and estimating prognosis. The stage of the disease is primarily assessed based on its spread at the time of initial diagnosis. It describes which lymph node regions, organs, and tissues of the body are involved and to which extent. The staging of some NHL (such as the large cell anaplastic lymphoma) also takes into consideration whether or not the patient has been experiencing B-symptoms (please see also chapter "Symptoms").

The most frequently applied staging system has, until recently, been the St. Jude's staging classification for childhood NHL (Murphy staging system). In 2015, this staging system was replaced by the so-called “International Paediatric Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Staging System" (IPNHLSS), which represents an extension and a more detailed version of the previous classification.

The IPNHLSS classification differentiates between four stages of disease (I-IV): Stage I corresponds to a single tumour inside or outside a lymph node (e.g. in the skin or bones), but not in the chest or abdomen. In stages II and III, more than one lymph node or other tissue/organ (including in the abdomen or chest) are affected. In addition to the possible tumour manifestations mentioned above, the most advanced stage of the disease (stage IV) is also characterised by an involvement of the central nervous system and/or bone marrow.

*Note to Stage IV: Lymphoblastic lymphomas revealing 25 % of bone marrow infiltration or more are not defined as NHL, but as acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL). Lymphoblastic lymphomas and ALL are biologically closely related, since they all arise from B- or T-cell precursors. Mature B-cell/Burkitt lymphomas presenting with 25 % of bone marrow involvement or more are known as Burkitt leukaemias, which represent a more advanced stage of the same disease, NOT a form of ALL. Patients with Burkitt leukaemia are treated as NHL patients.

Treatment

Treatment of children and adolescents with Non-Hodgkin lymphoma should take place in a children's hospital with a paediatric oncology program. Only such a treatment centre provides highly experienced and qualified staff (doctors, nurses, and many more) that is specialised and focussed on the diagnostics and treatment of children and teenagers with cancer according to the most advanced treatment concepts. The doctors in these centres collaborate closely with each other. Together, they treat their patients according to treatment plans (protocols) that are continuously optimised. The goal of the treatment is to achieve high cure rates while avoiding acute or long-term side effects as much as possible.

Treatment methods

Central backbone of treatment for patients with NHL is always chemotherapy. It uses drugs (so-called cytostatic agents) that can kill fast-dividing cells, such as cancer cells, or inhibit their growth, respectively. Since one cytostatic agent alone may not be capable of destroying all the lymphoma cells, a combination of cytostatics that function in different ways is given (polychemotherapy). The goal is to eliminate as many malignant cells as possible. In addition to chemotherapy, some few patients may also receive radiotherapy (for example radiation therapy of the brain) to increase the success of treatment.

Since NHL are so-called systemic diseases that affect the whole organism, surgery is usually not a feasible treatment option. It is only recommended for diagnostic reasons, such as removal of an affected lymph node for further analysis. In case of small tumours, this strategy can be used therapeutically, that means for complete tumour resection, too. Hence, a less intensive chemotherapy regimen may be sufficient in those patients. Completely sparing chemotherapy, however, is a very rare option (for example in patients with isolated skin involvement).

In certain situations, for example if the disease does not respond to standard therapy or in case of recurrent disease (relapse), high-dose chemotherapy may be necessary. The high doses of cytostatics given according to this treatment strategy are capable of eliminating even resistant lymphoma cells. Since high-dose chemotherapy also leads to the destruction of the blood-forming cells in the bone marrow, the patient will receive blood-forming stem cells in a second step. Usually, these blood stem cells are obtained from the bone marrow of a donor (allogeneic stem cell transplantation) or from the patient (autologous stem cell transplantation). Other treatment strategies (such as antibody therapy) are currently tested in the framework of different clinical trials.

Intensity and duration of chemotherapy, necessity of radiotherapy or stem cell transplant as well as the prognosis of the disease are primarily determined by the subtype of NHL, the extent of the disease at the time point of diagnosis (stage) and how the disease responds to therapy (see chapter "Treatment planning")

Course of treatment

Patients with Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) receive treatment according to various treatment protocols, which provide for different courses of therapy, depending on the subtype of NHL. All these protocols have in common that treatment, mostly chemotherapy, consists of multiple phases of therapy, which not only vary regarding their duration, but also the combination of chemotherapy, the intensity, as well as the goal of treatment. The treatment plans take into consideration the subtype of lymphoma, the extent of the disease, and additional factors (such as the affected anatomic sites), which represent every patient's individual situation.

The chemotherapeutic agents are usually given intravenously, as an infusion or injection, some are given orally as well. That way they get distributed in the blood system and can, thus, eliminate lymphoma cells throughout the whole body (systemic chemotherapy). In addition to this approach, some chemotherapy is given directly into the cerebrovascular fluid, which surrounds both brain and spinal cord (intrathecal chemotherapy). This is necessary because most chemotherapeutic agents cannot pass the barrier between blood and brain (blood-brain barrier).

The following paragraph will introduce the treatment plans for the three major NHL subtypes as per treatment recommendations of the current NHL-BFM registry 2012 (see chapter “Therapy optimizing trials and registries”). Please note that patients who are treated within trials may receive therapies other than the standard treatments described below. The studies are the current treatment standard in paediatric oncology.

Precursor B-cell and T-cell lymphoblastic NHL (LBL)

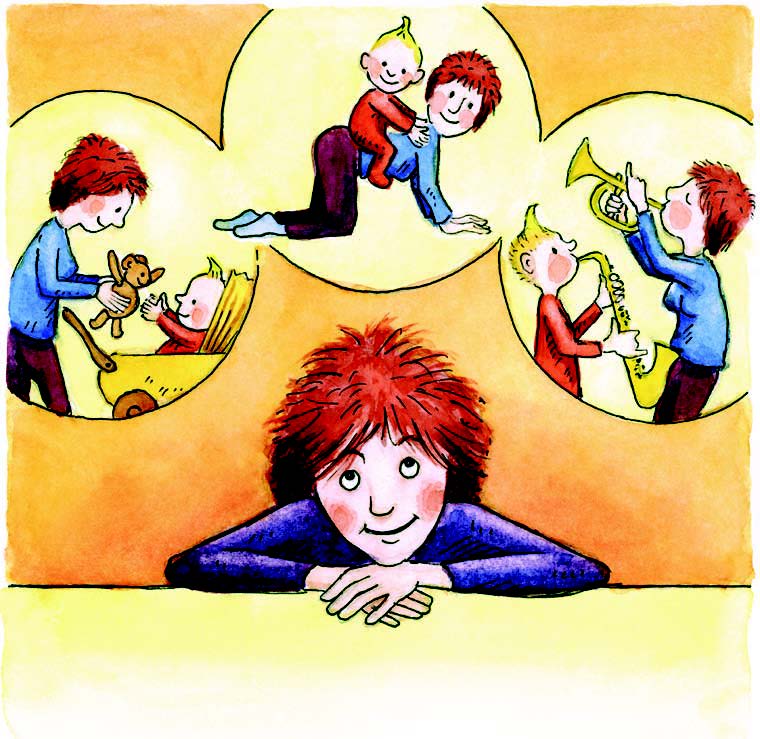

For patients with lymphoblastic lymphoma, a strategy containing multiple treatment phases (similar to treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, ALL), has proven to be a successful approach. The overall treatment duration takes about two years, unless the patient experiences progressive disease during treatment or relapse after cessation of therapy.

Important elements of treatment are:

- Pretreatment: The cytoreductive pre-phase is part of induction therapy. It serves the initiation of therapy and consists of a brief (about a week) chemotherapy with one or two different agents given intravenously or in tablets (orally). In order to also reach lymphoma cells in the central nervous system, another agent is given directly into the spinal canal (intrathecal chemotherapy, see section "CNS therapy" below). The goal of this pretreatment is to stepwise (and, thus, gently for the organism) reduce the initial burden of lymphoma cells, in order to prevent complications, such as tumour lysis syndrome.

- Induction therapy (protokoll I): The actual induction therapy involves a very intensive chemotherapy that includes multiple agents. In its first phase (protocol Ia), which takes about a month, it aims at eliminating as many lymphoma cells as possible and, thus, at achieving remission. The second phase of induction (protocol Ib) is supposed to destroy still remaining lymphoma cells, thereby minimising the risk of relapse, by using a different combination of chemotherapeutic agents. This phase also takes about four weeks. Similar to the ALL treatment regimen, protocol Ib is also known as consolidation therapy.

- Protocol M: Induction therapy is followed by a treatment phase that belongs to the extracompartment therapy (see below). It takes about two months and serves the treatment of the central nervous system and the testes. Depending on the stage of the disease, patients are then assigned to different treatment arms (such as maintenance therapy or reinduction followed by maintenance therapy, see subsequent section).

- Reinduction therapy (protocol IIa/b): Only patients with advanced stages of the disease (stage III or IV) will receive reinduction therapy. However, these patients represent the majority of patients with lymphoblastic NHL. (Patients with a very low risk of developing relapse will be assigned to the maintenance arm directly, see below.) The intensity of reinduction therapy is similar to that of induction therapy, which means that different combinations of chemotherapy are given with high dosages. The reinduction phase takes about seven weeks and serves to make sure that all lymphoma cells have been eliminated.

- CNS therapy (extracompartment therapy): An important part of the intensive treatment (consisting of pretreatment, induction, and reinduction) as well as of protocol M is the prophylactic or therapeutic treatment of the central nervous system (CNS). This extracompartment treatment aims at preventing lymphoma cells from settling in the brain and/or spinal cord or from spreading further within the CNS. CNS treatment usually involves multiple applications of CNS-feasible chemotherapy given into the spinal canal (intrathecal chemotherapy). If the CNS is involved in the disease already at diagnosis of the NHL, patients will also receive craniospinal radiation after the intensive chemotherapy phase. The duration of radiotherapy usually takes two to three weeks depending on the radiation dose. Children under one year of age do not receive craniospinal radiation therapy.

- Maintenance therapy: This last phase of treatment is designed to eliminate all the leukaemia cells that may not be detectable but still have survived the intensive treatment. The intensity of chemotherapy is much less than in the other phases. Also, the patient is mainly outpatient and may even continue with kindergarten or school. This phase of treatment is usually continued until a total treatment time of two years has been achieved.

Chemotherapy given for treatment of lymphoblastic NHL includes for example prednisone (PRED), vincristine (VCR), daunorubicin (DNR), E.-coli Asparaginase (ASP), cyclophosphamide (CPM), cytarabine (ARA-C), 6-thioguanine (6-GT), methotrexate (MTX), 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP), and dexamethasone (DEXA).

Note regarding treatment protocol LBL 2018: One goal of therapy optimising study LBL 2018 is to find out whether a different approach during induction (protocol 1a) may help reduce the development of recurrent disease with CNS involvement. In addition, the study is designed to evaluate whether an intensified treatment instead of standard therapy as per protocol 1b and protocol M will result in an increased relapse-free (event-free) survival of high-risk patients (see chapter "Therapy optimising trials and registries").

Mature B-cell Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (B-NHL) and acute B-cell leukaemia (B-AL)

The intensity of the treatment of mature B-cell NHL or acute B-cell leukaemia primarily depends on the stage of the disease and the initial burden of lymphoma cells. This burden (tumour mass) can be estimated well based upon the concentration of a specific enzyme in the serum (lactate dehydrogenase, LDH). Furthermore, treatment intensity is based upon whether a tumor could or could not be completely removed surgically. The entire duration of treatment usually takes between six weeks and six months, unless there is progressive or recurrent disease, respectively.

Important elements of treatment are:

- Pretreatment (cytoreductive pre-phase): It consists of a short (approximately five days long) phase of chemotherapy using moderate dosages of two different agents, which are given intravenously or in tablets (orally). In order to also reach lymphoma cells in the central nervous system (CNS), one or two additional chemotherapy applications are given directly into the spinal canal (intrathecal). The goal of this pretreatment is to stepwise and, thus, gently reduce the initial burden of lymphoma cells in order to prevent complications, such as tumour lysis syndrome.

- Intensive treatment: It consists of two to six intensive chemotherapy courses, each of which takes about five or six days, followed by an approximate three weeks' break of recovery. Chemotherapy includes multiple agents given intravenously, orally and also intrathecally. The goal is to eliminate as many lymphoma cells as possible with every single course. For patients after complete tumor removal, two courses of therapy are sufficient, all other patients require at least four courses in addition to the pre-phase. Patients with CNS involvement receive an intensified intrathecal chemotherapy. The duration of this phase usually takes between six weeks and six months, unless there is progressive or recurrent disease, respectively.

Chemotherapy given for treatment of these NHL subtypes includes for example dexamethasone (DEXA), cyclophosphamide (CPM), methotrexate (MTX), cytarabine (ARA-C), ifosfamide (IFO), etoposide (VP-16), doxorubicin (DOX), vincristine (VCR), vindesine (VDS) und prednisone (PRED).

Note to protocol B-NHL 2013: The therapy optimising study B-NHL 2013 is currently investigating whether the established combination chemotherapy regimen can be further improved by giving the antibody rituximab (see chapter "Therapy optimising trials and registries"). Rituximab is a synthetical (recombinant) antibody [see monoclonal antibodies , which specifically binds to the surface pattern of the B lymphocytes (the so-called CD20-antigen), thereby inducing cell death.

Anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL)

The type of treatment depends on the treatment group to which the patient has been assigned, based primarily on which organs and tissues are affected. Also, the potential complete removal of a lymphoma by diagnostic surgery is considered, however, this is only an option for a small number of patients. Patients with isolated skin involvement (rare) initially don't receive chemotherapy. The overall duration of therapy usually takes between ten weeks (for patients with stage I and after complete tumour removal) and five months, unless there is progressive or recurrent disease.

Important elements of treatment are:

- Pretreatment (cytoreductive pre-phase): It serves as the initiation of treatment and consists of a brief (usually five days) chemotherapy with two agents that are given intravenously and orally. In order to also reach lymphoma cells in the central nervous system, another agent is given directly into the spinal canal (intrathecal chemotherapy). The goal of this pretreatment is to stepwise and, thus, genlty reduce the initial burden of lymphoma cells in order to prevent complications, such as tumour lysis syndrome.

- Intensive therapy: It consists of three or six intensive courses of chemotherapy, each of which takes about five days and is followed by a short break of recovery. Patients with stage I disease receive three courses of chemotherapy, if complete removal of the tumor tissue was possible. All other patients receive six cycles of chemotherapy. Each cycle includes several different agents, some of which are given systemically (intravenously) and others orally. The goal is to eliminate as many lymphoma cells as possible with every single course. Patients with CNS involvement (very rare) also receive cranial radiation therapy.

Chemotherapy for treatment of ALCL includes dexamethasone (DEXA), cyclophosphamide (CPM), methotrexate (MTX), cytarabine (ARA-C), prednisone (PRED), ifosfamide (IFO), etoposide (VP-16), doxorubicin (DOX), and sometimes vindesine as well (VDS).

Note regarding trial ALCL-VBL: the current therapy optimising study ALCL-VBL 2018 examines whether outpatient vinblastine treatment of patients with standard risk ALCL will achieve as favourable results as the current polychemotherapy regimen. Precondition for such a treatment is that there are no remaining circulating lymphoma cells on a submicroscopic level (using sensitive diagnostics), thus having ruled out minimal disseminated disease. This is the case for about 40 % of the patients (see also chapter “Therapy optimising trials and registries”).

Therapy optimising trials and registries

In Germany, treatment of almost all children and adolescents with Non-Hodgkin lymphoma is performed according to the treatment plans (protocols) of therapy optimising trials or registries. The term “therapy optimising trial” refers to a form of controlled clinical trial that aims at improving current treatment concepts for sick patients based on the current scientific knowledge. With many treatment centres being involved in this kind of standardised treatment, such studies are also called “multicentred” and “cooperative”, and most often many countries participate.

Patients who cannot participate in any study, for example because none is available or open for them at that time, or since they do not meet the required inclusion criteria, respectively, are often included in a so-called registry. To ensure optimal treatment for patients not registered in a study, therapy is following the recommendations and advice of the treatment centre.

The following trials and registries for treatment of children and adolescents with Non-Hodging lymphoma are currently active in Germany (with international participation):

- NHL-BFM Registry 2012: international registry of the BFM study group for all children and adolescents with a newly diagnosed NHL, regardless of the subtype (BFM is the abbreviation for the cities Berlin, Frankfurt and Münster, where these treatment protocols have been designed initially). In mid 2012, the registry was opened after cessation of various therapy trials / registries with the goal to provide optimal treatment recommendations for NHL patients even in times without an active trial. A registry does not introduce new treatment strategies; it rather recommends the currently best available and optimal therapy based on preceding trials and the international literature for patients who have not been recruited to any trial.

- Trial B-NHL 2013: international therapy optimising trial for patients (under 18 years of age) with a mature B-cell lymphoma or mature B-cell leukaemia. The trial was opened in August 2017 and is conducted by the NHL-BFM study group and the Scandinavian study group (NOPH). Multiple childrens' hospitals and paediatric oncology programs in Germany, Austria, Switzerland, and the Czech Republic, as well as in Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden are participating. Goal of the trial is to improve the relapse-free (event-free) survival of the patients and a more rapid recovery of the immune system after cessation of therapy. Children with clearly localized disease (risk groups R1 and R2, stages I-II), are being assessed regarding the option of replacing previous chemotherapy with anthracyclines by a treatment with the anti-CD20 antibody rituximab see chapter “Course of treatment – mature B”.

- Trial LBL 2018: international therapy optimising trial of the NHL-BFM study group for patients under 18 years with a newly diagnosed lymphoblastic lymphoma. The trial was opened in September 2019, and multiple treatment centres in Germany as well as other European and additional countries are participating. One major goal is to reduce the risk of relapse (in high-risk patients by treatment intensification) and increase the probability of event-free survival for children and adolescents with lymphoblastic lymphoma.

- Trial ALCL-VBL: international therapy optimising study for patients (younger than 18 years of age) with newly diagnosed anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL). Eligible patients present with standard risk ALCL (ALCL stage I-III without minimal disseminated disease; see also chapter “Course of treatment – ALCL”). The study has been open in Germany since 2021 and is currently starting in all European as well as other non-European countries. Goal of the study is to find out whether children treated by outpatient vinblastine therapy fare as well as patients receiving standard polychemotherapy.

The registry is under supervision of Prof. Dr. med. Birgit Burkhardt (Universitätsklinikum Münster) and Prof. Dr. med. Wilhelm Wößmann (Universitätsklinikum Hamburg-Eppendorf). Principal Investigator for the trials LBL 2018 and B-NHL 2013 is Prof. Dr. med. Birgit Burkhardt (Münster), for the trial ALCL-VBL Prof. Dr. med. Wilhelm Wößmann (Hamburg).

Prognosis

The chances of cure (prognosis) for children and adolescents with newly diagnosed Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) have significantly improved due to the immense progress in diagnosis and treatment over the last four decades. Today’s modern diagnostic procedures and the use of intensive, standardised polychemotherapy protocols have resulted in long-term survival of the majority of children and adolescents with NHL (the 5- to 10-year survival rate is currently at about 90 %).

The prognosis for the individual patient primarily depends on the subtype of NHL and the extent of the disease (stage) at the time point of first diagnosis.

Patients with NHL stage I (meaning with one single tumour) have a very good prognosis (with a 100 % probability of survival). Patients with stage II disease also have a favourable outcome. If the chest and/or abdomen are/is involved (stage III) or the central nervous system and/or bone marrow (stage IV), however, intensified therapy is required, which usually also results in good cure rates..

About 10-15 % of children and adolescents with NHL develop recurrent disease (relapse). Prognosis for these patients is generally unfavourable, even though for some of them (for example those with anaplastic large cell lymphoma or diffuse large cell B-cell lymphoma), outcomes are a bit better. The current therapy optimising trials and future studies aim at improving the chances of cure for these patients, too.

Note: The survival rates mentioned in the text above are statistical values. Therefore, they only provide information on the total cohort of patients with childhood NHL. They do not predict individual outcomes. NHL can show unpredictable courses, in both patients with favourable and patients with unfavourable preconditions.

Literaturliste

- Stanulla M, Erdmann F, Kratz CP: Risikofaktoren für Krebserkrankungen im Kindes- und Jugendalter. Monatsschrift Kinderheilkunde 169, 30-38 2021 [DOI: 10.1007/s00112-020-01083-8]

- Erdmann F, Kaatsch P, Grabow D, Spix C: German Childhood Cancer Registry - Annual Report 2019 (1980-2018). Institute of Medical Biostatistics, Epidemiology and Informatics (IMBEI) at the University Medical Center of the Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz 2020 [URI: https://www.kinderkrebsregister.de/ typo3temp/ secure_downloads/ 42507/ 0/ 1c5976c2ab8af5b6b388149df7182582a4cd6a39/ Buch_DKKR_Jahresbericht_2019_komplett.pdf]

- Burkhardt B, Klapper W, Woessmann W: Non-Hodgkin-Lymphome. in: Niemeyer C, Eggert A (Hrsg.): Pädiatrische Hämatologie und Onkologie. Springer-Verlag GmbH Deutschland, 2. vollständig überarbeitete Auflage 2018, 324 [ISBN: 978-3-662-43685-1]

- Burkhardt B, Wössmann W: Non-Hodgkin-Lymphome. S1-Leitlinie 025/013: Non-Hodgkin-Lymphome im Kindes- und Jugendalter 2017 [URI: https://www.awmf.org/ uploads/ tx_szleitlinien/ 025-013l_S1_Non-Hodgkin-Lymphome_NHL_2017-05-abgelaufen.pdf]

- Rosolen A, Perkins SL, Pinkerton CR, Guillerman RP, Sandlund JT, Patte C, Reiter A, Cairo MS: Revised International Pediatric Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Staging System. Journal of clinical oncology 2015, 33: 2112 [PMID: 25940716]

- Thorer H, Zimmermann M, Makarova O, Oschlies I, Klapper W, Lang P, von Stackelberg A, Fleischhack G, Worch J, Jürgens H, Woessmann W, Reiter A, Burkhardt B: Primary central nervous system lymphoma in children and adolescents: low relapse rate after treatment according to Non-Hodgkin-Lymphoma Berlin-Frankfurt-Münster protocols for systemic lymphoma. Haematologica 2014, [PMID: 25107886]

- Reiter A: Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma in Children and Adolescents. Klinische Padiatrie 2013, 225(S 01):S87-S93 [PMID: 23700066]

- Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, Thiele J, Vardiman JW (Eds): WHO Classification of Tumours of the Haematopoetic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon, France: IARC Press 2008, 109

- Le Deley MC, Reiter A, Williams D, Delsol G, Oschlies I, McCarthy K, Zimmermann M, Brugières L, European Intergroup for Childhood Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma: Prognostic factors in childhood anaplastic large cell lymphoma: results of a large European intergroup study. Blood 2008, 111: 1560 [PMID: 17957029]

- Salzburg J, Burkhardt B, Zimmermann M, Wachowski O, Woessmann W, Oschlies I, Klapper W, Wacker HH, Ludwig WD, Niggli F, Mann G, Gadner H, Riehm H, Schrappe M, Reiter A: Prevalence, clinical pattern, and outcome of CNS involvement in childhood and adolescent non-Hodgkin's lymphoma differ by non-Hodgkin's lymphoma subtype: a Berlin-Frankfurt-Münster Group Report. Journal of clinical oncology 2007, 25: 3915 [PMID: 17761975]

- Ferris Tortajada J, Garcia Castell J, Berbel Tornero O, Clar Gimeno S: Risk factors for non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. An Esp Pediatr 2001, 55: 230 [PMID: 11676898]

- Reiter A, Schrappe M, Ludwig W, Tiemann M, Parwaresch R, Zimmermann M, Schirg E, Henze G, Schellong G, Gadner H, Riehm H: Intensive ALL-type therapy without local radiotherapy provides a 90% event-free survival for children with T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma. Blood 2000, 95: 416 [PMID: 10627444]

- Murphy SB: Classification, staging and end results of treatment of childhood non-Hodgkins-lymphomas: dissimilarities from lymphomas in adults. Semin Oncol 1980, 7: 332 [PMID: 7414342]

PDF Brief Information on NonHodgkin lymphoma (503KB)

PDF Brief Information on NonHodgkin lymphoma (503KB)